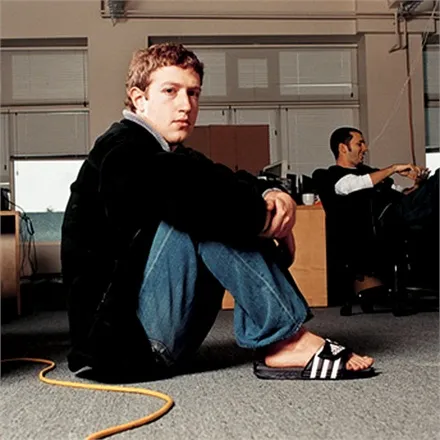

Young Mark Zuckerberg sitting in a garage, c. 2005

« Move Fast, Break Things »? It’s giving 2005.

Facebook’s early mantra of « move fast and break things » has become a common refrain in the startup world and somewhat of an oversimplified caricature of Silicon Valley culture – specifically the subculture stemming from the late 90s and early 2000s. While dot-com era companies and early social networking sites such as Amazon, Google, and Facebook have leveraged network effects to become some of the most successful companies of our time, the transition from principle to real-life application isn’t so simple for later-generation startups today.

Originally coined by Mark Zuckerberg, the founder of Facebook, the phrase « move fast and break things » has become a popular and controversial one-liner prescribing the kind of attitude Zuckerberg thinks founders should have with regard to creating, growing, and scaling their companies, especially for those specializing in software and services that become more valuable as more people adopt it – a classic example of network effect principles in action. Examples of such services include social networking sites such as Facebook, payment platforms such as PayPal, messaging platforms such as Whatsapp, marketplaces such as Amazon, and collaborative tools such as Slack.

At the core of the urgent imperative to grow and scale as quickly as possible is the concept of the « minimum viable network.” When a startup wants to establish a stable presence in the market upon entry, it needs to establish what is called a “minimum viable network” for its product. In order to leverage network effects, startups need to first achieve a critical mass of users, beyond which the value of the network begins to increase exponentially in a J-shaped curve. The idea is that by moving fast and aggressively acquiring users, startups can reach this critical mass more quickly and even have a special advantage to be in the lead over other competitors – i.e., if a startup became the first and biggest network in its market, it would essentially become unstoppable. Here, the key idea is that the value of a network grows exponentially with the number of users, and hence, one of the most effective ways for startups to achieve sustainable growth is by building and compounding upon network effects.

I am not a fan of the hypercompetitive, heedless rhetoric of the “move fast and break things”’ mantra, which places a heavy emphasis on the “first mover advantage” and the idea of the “J-shaped hockey-curve.” These concepts, which are helpful in understanding the theoretical advantages of network effects and can be immensely relevant when understood within the context of larger socio-psychological influences and other stochastic forces, do not translate in such a straightforward way in real life, and those that have the blind confidence to think so would be stuck in the the 90s and early 2000s, which were much simpler and more reckless times in Silicon Valley. The “first mover advantage,” essentially a derivation of the “rich-get-richer” principle, is largely a myth, as the winner is usually a later entrant. Similarly, the J-shaped trajectory of growth does not magically appear after a company has reached its critical mass of early adopters. In other words, not only does scaling a company require an immense amount of energy for strengthening the network effects and fighting off competition and market saturation, but it also requires a lot of focus on the right problems, which can vary across industries and shift with the different stages of a startup’s maturation.

There is also good reason to be concerned about the potential downsides and ethical implications of a mindset that prioritizes winning above all costs, especially when it is taken as legitimate advice without a grain of salt. Startups that are too aggressive in their pursuit of growth may risk alienating users or sacrificing long-term sustainability for short-term gains – for example, achieving fast growth at the expense depriving its user base of their attention capital or mental health integrity, or at the risk of creating a toxic and cutthroat internal culture within the company. Additionally, disruptions to the network can have ripple effects that harm the user experience and erode trust in the platform.

Andrew Chen, a partner at a16z, addresses the inaccurate thinking of expecting network theory to apply perfectly to an imperfect and messy world in his book The Cold Start Problem. The book explores the challenges faced by startups in their early stages, when they lack the network effects and data that established companies can rely on to drive growth. The “cold start problem” refers to the challenge of starting a new business without an existing user base or network effects to leverage. This can make it difficult for startups to attract users and achieve rapid growth, especially in highly competitive markets. In order to overcome the cold start problem, Chen posits that startups need to focus on user acquisition and create a strong value proposition that will not only attract early adopters, but the right early adopters.

Chen argues that the “move fast, break things” principle is largely irrelevant for many startups in today’s competitive landscape for a handful of reasons.

-

The first reason is that quality matters more than quantity. According to Chen, in today’s market, the quality of a user’s engagement with a product or service is more important than the number of users. For example, a network with a large number of inactive or low-quality users may not be as valuable as a smaller network with highly engaged users.

-

Second, network effects are not always positive. While network effects can certainly be a powerful driver of growth, they are not always positive. For example, negative network effects can occur when a network becomes too crowded or spammy, leading to a decline in user experience and value.

-

Third, other factors, such as user experience, product-market fit, and marketing effectiveness, are often more important than network effects in determining a startup’s success. These factors can play a critical role in helping a startup overcome the cold start problem and achieve sustainable growth.

Overall, while network effects can certainly be a powerful driver of growth for startups, they should not be relied on as the sole factor in determining a startup’s success. Instead, startups should focus on creating high-quality user experiences, achieving product-market fit, and implementing effective marketing strategies in order to overcome the cold start problem and achieve sustainable growth.

Book Reference:

Chen, Andrew. The Cold Start Problem. HarperCollins. Kindle Edition.